In early November I had the honor to speak at the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) Roundtable on Aligning Incentives for Open Science. This Roundtable has been convening thought leaders and stakeholders to identify the whats, whys, and hows of open science policies and incentives. I was invited to provide a researcher perspective and opinions on priorities for funding open science. The first part of this post is a summary of my talk. The second part is some ideas about the Roundtable’s draft Toolkit a document primarily intended for university leadership, academic department chairs, research funders, and government agencies audiences. Ideas about the Toolkit are from discussions with Erin Robinson.

Update October 2021:

NASEM’s report Developing a Toolkit for Fostering Open Science Practices was published! This includes a 2.5 page summary of our talk outlined below.

Quick links:

- my slides

- Roundtable on Aligning Incentives for Open Science

- Roundtable Workshop & Toolkit

- SPARC Impact story

- Developing a Toolkit for Fostering Open Science Practices - NASEM Report

How to empower researchers with open science

My talk was called “How to empower researchers with open science through meeting analytical needs and supporting people”. The main point was that we can normalize open science through addressing the analytical needs of research teams, and that we must fund people that are already working to make this happen and grow the open movement.

In developing those ideas throughout my talk, I also focused on how open science is a behavior that we can support researchers to practice, and that a critical part of open science is that it helps promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in modern science. Additionally, open leaders do jobs that aren’t currently valued in academia, and they are critical to helping normalize open science.

I think that data science should play a bigger part in open science conversations; I have seen that data science and open science conversations often happen separately. But data analysis is a really critical place to focus efforts for open science, because working with data is something that all researchers do, and it starts early and extends throughout the research process. That means data analysis can make open science truly be a daily activity, something that isn’t the case when we think about open science mostly as publishing or other products/artifacts. Supporting researchers to learn open practices for data science — “open data science — empowers researchers by meeting their analytical needs and turns open science from an idea to a daily benefit. I have been defining open data science as the tooling and people enabling reproducible, transparent, inclusive practices for data analysis.

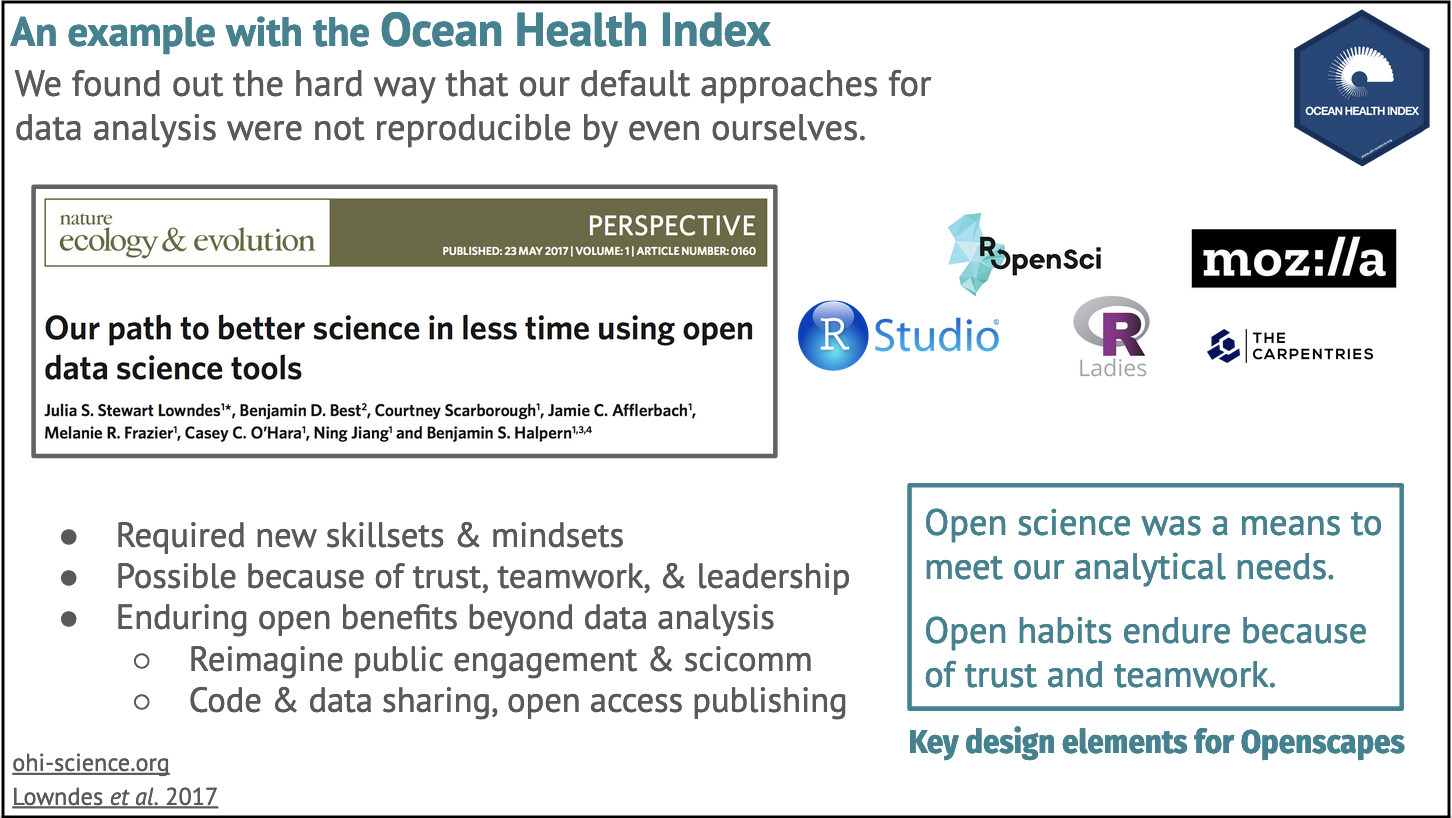

After describing how open data science is powerful like the Force from Star Wars (see my slides with artwork by Allison Horst), I gave an real-life research example with the Ocean Health Index.

Our Ocean Health Index team found out the hard way that our default approaches to data analysis was not reproducible by even ourselves. Getting through this involved quite a reckoning, but when we got through it, we knew we had a story to tell.

Two big lessons coming out of the Ocean Health Index story was first that open science was a means of meeting our analytical needs. Open science was not a goal in itself, but a secret power that was unlocked through engaging with the open community. And the second is that the open habits we developed are enduring because they are built on trust and teamwork. These two things have been key design elements for Openscapes, which I founded last year with a fellowship from Mozilla.

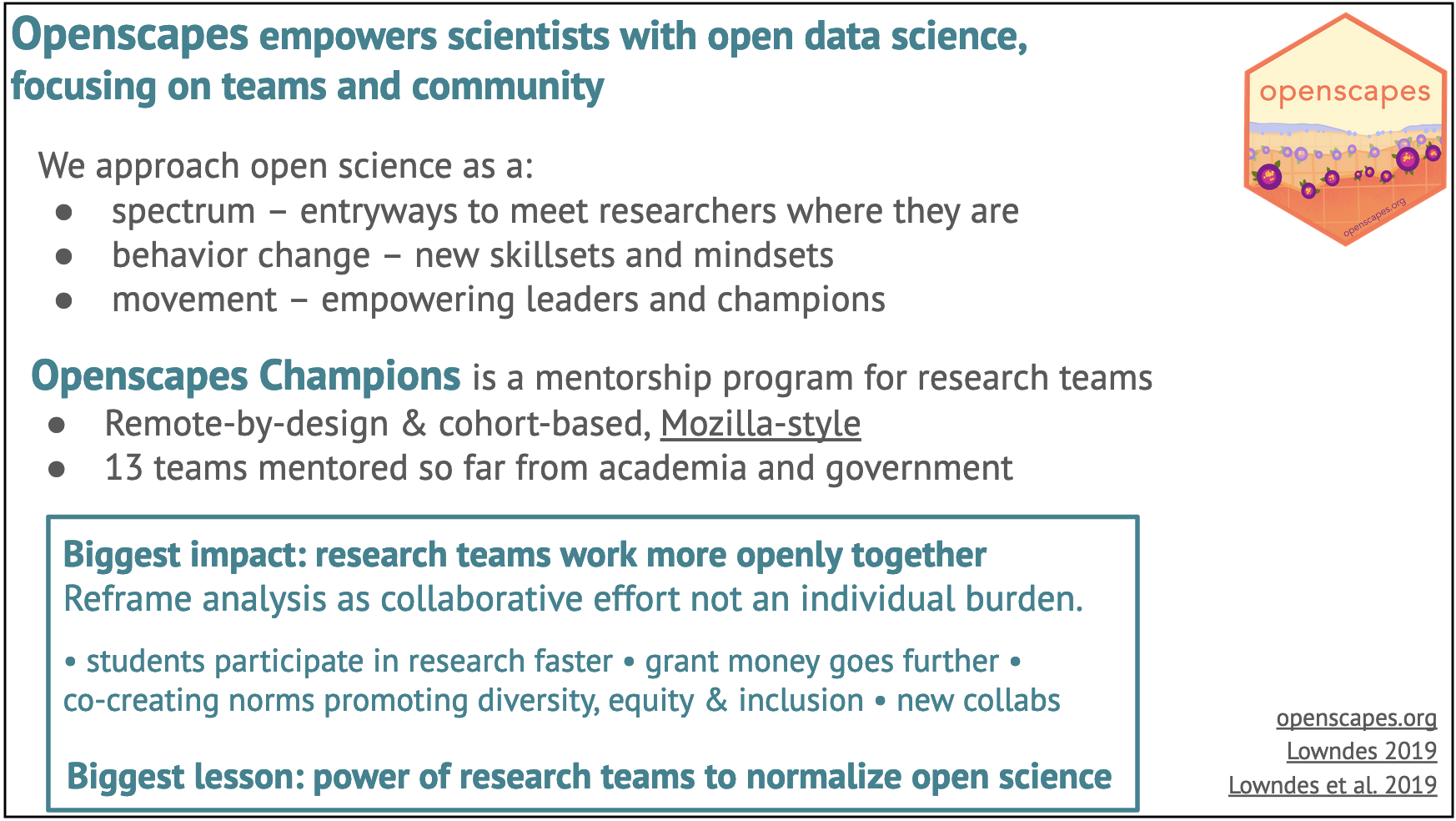

I built Openscapes to empower scientists with open data science, focusing on teams and community. We approach open science as a spectrum, a behavior change, and a movement. We use data analysis as an entryway to meet scientists where they are, and help develop new skillsets and mindsets but also focus on empowering them as leaders and champions for open science.

The main way we do this is through Openscapes Champions, which is a mentorship program for research teams. It’s remote-by-design & cohort-based, which enables community building across research teams and universities and develops skills for collaborating remotely. I’ve mentored 13 PIs and their team members so far from academia and government, and I have a waiting list of folks that want to participate.

The biggest impact is that research teams are working more openly together. They’ve been able to do this by reframing data analysis as a collaborative effort rather than an individual burden. And what we see from that is that students are able to participate in research faster, grant money is going further, and teams are co-creating norms that promote diversity, equity and inclusion, and emerging collaborations across research groups.

And the biggest lesson is the power of teams for normalizing open science. When we talk about open science it’s often about participating publicly. But the truth is, when researchers aren’t working openly within their research group, it’s hard to expect them to work openly in the public sense. So focusing on empowering teams to feel confident collaborating openly together can really catalyze enduring change. And developing efficiencies and resilience within the research group is an immediate benefit to the research group, so there is motivation and incentive to participate and develop these habits with the right support.

Finally, I focused on priorities for funding open science. I see supporting people as a huge unmet need.

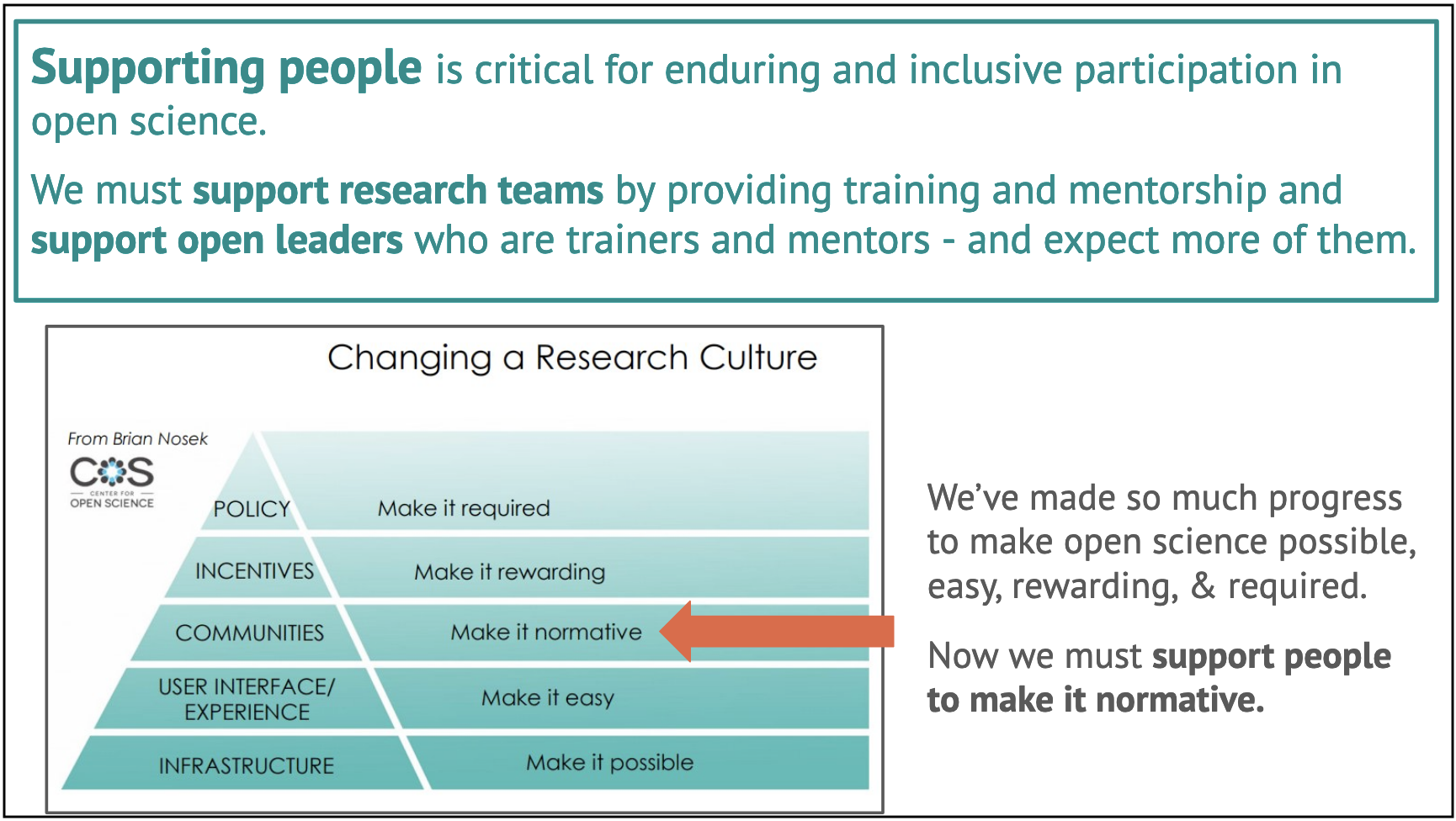

Center for Open Science

I really like this figure from Brian Nosek at the Center for Open Science that shows how to change a research culture (I first saw it in a talk by Karthik Ram). Thanks to so much of the efforts of folks at the NASEM Roundtable, we’ve made so much awesome progress to make open science possible, easy, rewarding, and required. Now we must support people to make it normative. We need to invest in the human infrastructure that will make this possible. I had two suggestions, following on the themes from my talk that are possible to do now:

First: sponsor research teams to be trained and mentored by existing efforts. This means paying for seats so researchers can attend Hackweeks, Meetups, Carpentries workshops, Openscapes cohorts with their other research team members. The benefits are to help meet existing needs with existing programs, and it’s little cost, and we can do it now.

Second: pay the salary for open leaders who train and mentor research teams. We already exist in academia by various unofficial titles: we are trainers, mentors, research software engineers, community managers. We are often early career, on soft money, with no job security or career path. Creating jobs for us is the ultimate goal but what’s needed right now is to pay our salaries so we can continue doing our work. The benefits are that trainers can focus on training, which meets this critical need and increases continuity of services, and importantly it also reduces the burnout that comes when open leaders do this without full funding and causes them leave academia, which then further delays open science progress.

My last point at the end of my talk was that open leaders do jobs that aren’t currently valued in academia, and they are critical to helping normalize open science. And, we should expect more of them and be prepared to support them in salaried university roles in the future.

Ideas from the Toolkit

The NASEM Roundtable on Aligning Incentives for Open Science’s Toolkit is organized in several sections, including Primers that give high-level overviews of open sharing on topics like articles, code & software, data, and reporting; an Open Science Imperative Essay about the benefits of open science; and a Sending Signals Rubric with language for signaling open science at specific points of high leverage. Here are some thoughts I’ve discussed with Erin Robinson, who has been participating at the Roundtable convenings. She has already been using the Toolkit to guide research statements and reference letters, and we’re interested to bring these concepts to Openscapes Champions cohorts as well.

Open Science Imperative Essay. There was some language that really resonated for us:

“Historically, academic research environments have incentivized competition between individual researchers, which stymies collaboration and leads to the hoarding of knowledge”

“Open Science practices, in contrast to traditional models of knowledge production, emphasize that open, transparent, and collaborative research dissemination practices more properly balance collective, institutional, and individual benefits. Open Science represents a positive evolution of the research endeavor along three dimensions: Collaboration drives innovation with the potential for broad social impact; Greater efficiency and speed; Replicability enhances trust and research quality”

“Fortunately, the values that underpin Open Science – such as inclusiveness, collaboration, social impact, and scientific literacy – are mutually reinforcing to the missions of the research institutions, agencies, and funding organizations that support scientific research. Forward- thinking organizations have already begun to implement incentives for Open Science practices that provide a model for others to follow, which have taken several forms including: creating supportive environments”

These quotes resonated because they are about Open Science practices that interplay with support and collaboration. It is critical to focus on open practices along with open products, which are more readily measurable and thus have gotten a lot of the attention. It is fantastic to see them in the stated up-front, as mutually reinforcing with the missions of research institutions. These ideas are central to Openscapes, where we help create supportive environments centered on data science that drive collaboration, innovation, and efficiency, which are all part of the daily practice and benefits of Open Science.

Sending Signals Rubric. This rubric has four stages to help identify participation in Open Science. It seems like it would be really useful for other usecases beyond the hiring and tenure instances that it was developed for. For example, Openscapes may be able to use it as short-term indicators to understand where participating teams begin (likely Stage 1 or 2) and where they are at the end of the program, and months later. Likely the most useful version in this usecase timescale will be the “other outputs version”, so that participants can get credit for sharing teaching materials, Codes of Conduct, presentation slides and recordings, etc.

Primers. The Primers are 1-2 page high-level overview of the what’s and how’s of open sharing. They are organized in a really helpful way, introducing topics like articles, software, and data through their relevance to the open ecosystem, considerations, approaches, and resourcing. A comment is that they do all focus on products rather than behaviors, with guidance centering on the logistics and auditing side of making these products open without mention of the training and support scientists need to create open products. For example, the code and software section assumes that researchers are writing code, and code that is written ways that can be easily run independently by others on their computers (with appropriate licensing, etc). But coding and working openly and responsibly with data analysis is rarely taught in universities, making training in data analysis an unmet need — something that is being perpetuated to future scientists because self-taught scientists don’t feel comfortable teaching computing practices to undergrads. So, as we continue discussing goalposts for Open Science we need to think about the support we’re providing for researchers to be able to successfully meet those goalposts.

Supporting the people required to enable Open Science could be reflected in the Primers’ Resourcing sections in the Toolkit. Many of the Primers have a statement that say “Administrators may be concerned about how policy changes can create additional operational work to already busy staff.” Yes — there is a lot of work involved to help normalize Open Science, and it will take more people and new jobs. We cannot expect to have already busy staff squeeze this in — we need to support open leaders and champions with valued jobs to help make this happen. From a recent post on FORCE11’s blog by Kaitlyn Thaney:

“An additional dimension to our work involves looking at the staffing and human infrastructure powering open technology development, maintenance, governance and stewardship. That volunteer labor and community engagement is often an invisible cost we gloss over in our estimations and recommendations, while also being a core pillar in this work.”

Finally, something missing from the Toolkit is how Open Science efforts must promote diversity, equity, and inclusion. There were several speakers at the November 5 Roundtable that spoke about diversity and inclusion in open science, so hopefully there are plans to weave this prominently into the Toolkit as well. There are many fantastic resources available, including Mozilla’s Inclusion and Governance Checklist and Abigail Cabunoc Mayes’s work on Working open as a way to shift power. We have been incorporating these ideas into Openscapes since the start, since our Champions mentorship program is modeled after Abby’s Mozilla Open Leaders, and thus prioritizing diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging is reflected in our language, our mentoring and engagement, our publications and presentations, our grant proposals. There is a lot of opportunity for Open Science to include and empower diverse participation, and Openscapes is excited to help.